By Pedro Burgos

Over the past decade or so, people have grown suspicious of the ability to learn much through online debate. We’re surrounded by articles about our cognitive biases, and the logical fallacies that appear in online discussions.

A number of books such as You Are Not So Smart as well as theories on “motivated reasoning” state that we’re much more stubborn than we think. A combination of political polarization and the rise of movements such as anti-vaxxers and climate–change deniers have given rise to greater levels of cynicism among engaged internet users. If we can’t agree on basic reality or facts, how can we discuss who is right and who is wrong?

One option is to put aside the contentious notion that the point of a debate is to convince someone. An argument may have intrinsic value on its own. Christopher Hitchens famously wrote that “Time spent arguing is, oddly enough, almost never wasted.” Entering into an argument could be seen as an exercise in testing your reasoning and encouraging you to fact check your own ideas – which could be very useful for future discussions among people with whom you usually agree.

After many years of research, including running a highly engaged website community at Gizmodo Brasil, I believe there are some principles that would hugely improve how you interact with those you disagree with online.

They’re not for everyone – many people seem to enjoy not engaging in actual discussion, focusing only on name calling. However, if everyone in an online discussion space succeeds in engaging on these terms, I think the results speak for themselves.

Let me know if you agree.

Pedro’s Guide to Constructive Disagreement

1. Talk about something you know

2. Choose your interlocutor/s carefully

3. Make sure that you understand the opposing arguments

4. Identify agreements

5. Do your research

6. Don’t reply too quickly

7. Dig deeper

8. Know when to stop

9. Carefully state the disagreement and then stop

1. Talk about something you know

You can learn a lot by debating subjects about which you don’t have much knowledge, but chances are that other people probably won’t productively debate your points if your argument is weak from the start. When entering in an online debate, try to choose something of which you have at least some familiarity, but about which your views aren’t completely immutable.

2. Choose your interlocutor/s carefully

Remember, the people you engage with are not your enemies, just people who hold ideas that you might disagree with. But if you spot ad-hominem attacks or straw man fallacies in their words, think carefully about if you’re only really engaging them because they irritate you.

3. Make sure that you understand the opposing arguments

As philosopher Daniel Dennett wrote, when you want to criticize an idea, “you should attempt to re-express your target’s position so clearly, vividly, and fairly that your target says, ‘Thanks, I wish I’d thought of putting it that way.'” Work on writing responses without being snarky or condescending. Rephrasing your opponent’s point of view will also make your disagreement clearer. If you want to practice your dialectic chops, go to a place designed for recreational argument.

4. Identify agreements

Finding common ground and starting your reply with a point of agreement is a good way to show your opponent that you have at least some respect for their argument. Even if you don’t agree with anything they say, show that you at least understand it by restating some or all of it as you begin. The vast majority of people you encounter online want to achieve the same goal, but differ (sometimes substantially) in terms of how they try to attain it. If you don’t assume beforehand that people you disagree with person are evil, or have ulterior motives, and so they don’t feel instantly judged by you, then there’s a greater chance that they will listen to what you have to say.

5. Do your research

You have to support your arguments with facts, and fact-check your opponent’s words. This is a good opportunity to learn new things. One trick: many of the common discussions I see online lately (particularly on the American elections) have been fact-checked by the website Politifact. You can start your research there. Be careful using sources that the opponent can easily dismiss, such as news sources that lean heavily in one political direction or another.

6. Don’t reply too quickly

It’s tempting to throw out a dismissive response, but an interesting argument can easily be ruined by an angry or sarcastic line. The best way to avoid the temptation of writing one is to take time away from the discussion when you read something that pisses you off. That also gives both parties a chance to let the arguments made so far sink in. The web is asynchronous. Use it to your advantage.

7. Dig deeper

The most useful part of an “unwinnable” argument is when you spot what makes the differences irreconcilable. In philosophy, that’s called the epistemic principles. One example is an evolution vs. creationism debate: if a belief in God and the Bible informs your opinions, there’s very likely a limit to how much you will concede in an argument over evolution (but your views may be more nuanced than you are given credit for.)

If you can identify some of the guiding principles of your opponent’s reasoning, you might not just learn how to approach them with your argument, but also learn how people with a different set of beliefs value things in a different way. Just be careful not to rely on stereotypes, or to assume that all people who have one set of beliefs think the same way.

8. Know when to stop

A recent study suggests that the chances of a person “changing the view” of another in an online argument fall dramatically after just five replies. By that point, we often are simply rephrasing what has already been said. Try to avoid this by constantly reassessing the discussion to see if the “core disagreement” has been identified, or if you are all repeating yourselves. If you’re just saying the same thing back and forth, then you might find it more productive to find another discussion on the topic.

9. Carefully state the disagreement and then stop

If you lose an argument, you win some knowledge. If you win an argument, then you gain an ally. If you end in a stalemate, which is by far the most likely result, then try to rephrase your opponent’s argument and yours succinctly in a single comment so that everyone has an opportunity to win some appreciation for the debate. You can recognize that the disagreement comes from the fact that you and the opponent see the world through different lenses, and acknowledge what you’ve learned from that recognition. Such a display of empathy could help all sides respect other points of view, and engage in respectful debate some time in the future, even if their minds aren’t changed.

—

Pedro Burgos is a Brazilian Journalist with an M.A. in Social Journalism from CUNY Journalism School. He wrote a book in Portuguese about living a healthy life online, and is currently working at The Marshall Project as an Audience Intern.

Further reading:

You Are Not So Smart podcast – “Arguing, with Hugo Mercier”

Aeon Magazine – “Not so foolish”, by Steven Poole

In Praise of Reason: Why Rationality Matters for Democracy – Michael P. Lynch

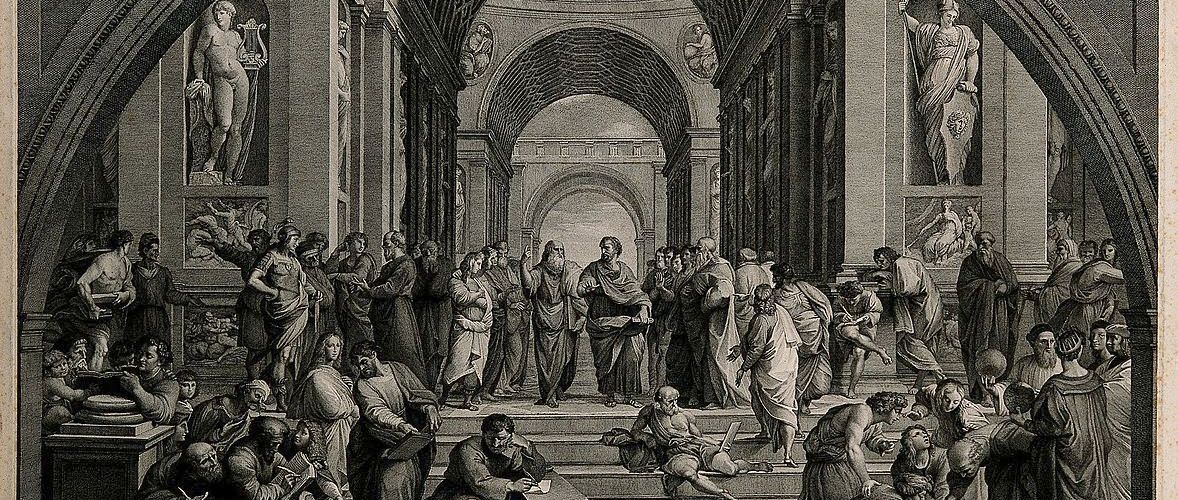

Image by J Volpato “The School Of Athens” shared under CC-BY-4.0